AN ARTIST'S JOURNAL

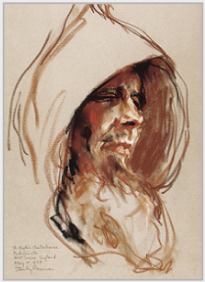

Edited and prepared for the Internet by Ronald Davis

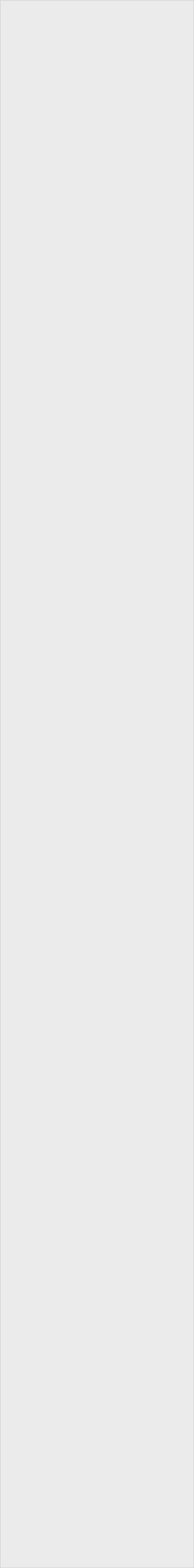

Dom Henry,

Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978

St. Augustine's Abbey, Kent, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978

St. Augustine's Abbey, Kent, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

''No one, I believe, in 1,500 years of Christian monachism has catalogued, defined

and described so clearly or so beautifully the business of the monastic life.

No writer, no sculptor, no painter, no architect has refined a distillation so pure,

so accurate, so breathtakingly clear as Roseman has done.''

and described so clearly or so beautifully the business of the monastic life.

No writer, no sculptor, no painter, no architect has refined a distillation so pure,

so accurate, so breathtakingly clear as Roseman has done.''

Stanley Roseman embarked in 1978 on what the Los Angeles Times praises as ''a sweeping artistic project.'' The artist was invited to live in Benedictine, Cistercian, Trappist, and Carthusian monasteries and to share in the day-to-day life in the cloister. Behind the monastery walls, Roseman painted portraits and made drawings of monks and nuns of the four monastic Orders in the Western Church and created a monumental and critically acclaimed oeuvre on the monastic, or contemplative, life.

"The word 'monk' derives from the Greek monachos, having as its root monos, meaning 'one' or 'singular,' 'alone' or 'apart from.' The monastic life, which reaches back to the Early Church, centers on contemplation, prayer, and the celebration of the Divine Office in observing the Biblical calls to prayer stated by the Prophet in the Book of Psalms: 'I rise to praise you at midnight, O Lord,' and 'Seven times a day I praise you.'

Correct Usage of the Word "Monk''

in reference to Male Members of Religious Orders

in the Western Church

in reference to Male Members of Religious Orders

in the Western Church

The word "monk"

Roseman's ecumenical work, brought to realization in the enlightenment of Vatican II, depicts monks and nuns of the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran faiths. Roseman created his work in over sixty monasteries throughout England, Ireland, and Continental Europe. The artist writes: ''When I began researching and planning my work on the monastic life, my thoughts were towards Europe for monastic life is interwoven with the history and culture of Europe. . . ."

"The Mendicant Orders began in the early thirteenth century and include the Order of Friars Minor, or Franciscans; Order of Friars Preachers, or Dominicans; Order of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, or Carmelites; and Austin Friars. Franciscan and Dominican friars were common to the cityscape and sought contact with society in contrast to those who sought the contemplative life behind the monastery walls.

"C. H. Lawrence, Professor of Medieval History, writes: 'The order of mendicant friars which appeared early in the thirteenth century represented a new departure, a radical breakaway from the monastic tradition of the past. . . . Preaching and ministering to the people was the raison d'être. . . . Unlike the monk, who is bound to the house of his profession, the friar is mobile.'[7]

"The Benedictine monk and historian Dom David Knowles, relating the origins of the Mendicant Orders, writes of St. Francis and St. Dominic: 'Between them they created a new kind of devotee, the friar, whose aim was not solitude or seclusion from the world and whose occupation was not primarily liturgical worship, but who went up and down the ways of men calling them to the following of Christ and preaching to them Christian doctrine.'[8]

"Sir Richard Southern further writes in Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages: 'The friars were basically a Mediterranean and urban movement. . . . Wherever there was a town, there were friars; and without a town there were no friars. . . . Their whole way of life depended on the association with the town, and this determined the direction of their later development.'[9]

"The different religious orders were established for different reasons," Roseman states, "and those distinctions should be respected in writing of them. It is incorrect to refer to a 'Dominican monk,' 'Carmelite monk,' or 'Franciscan monk.' The correct terminology is 'Dominican friar,' 'Carmelite friar,' and 'Franciscan friar.' Professor Wolfgang Braunfels, Director of the Art History Department of Munich University, states: 'The Franciscans did not want to be monks, they never tried to withdraw from the world into monasteries. . . . Nonetheless St Francis was willing to be tonsured, denoting that he was, if not a monk, then still a cleric.' "[13]

Monks and Other Male Religious in Art

An Unprecedented Work on the Monastic Life

When Roseman began painting and drawing in monasteries in the late 1970's, monastic life was little known to the general public and an unfamiliar subject for a modern artist's work. Monastic life was rarely a topic for coverage in the popular press.

The respected art journal ARA arte religioso actual, Madrid, published in the fall of 1979 a laudatory reportage entitled ''Stanley Roseman y la Vida Monastica'' and states:

''The pictures - splendid and telling all at once - form the stimulating vanguard

towards so original and deep a study of the monastic life.''

towards so original and deep a study of the monastic life.''

- ARA arte religioso actual, Madrid

You are cordially invited to visit www.stanleyroseman-monasticlife.com

Roseman's interest in monasticism, his in-depth studies on the subject, and the encouragement of monks and nuns whom he came to know through his work led the artist to write a text to accompany his paintings and drawings on the monastic life.[1] The editor of this website has prepared this page with an explanation by Roseman addressing the misuse of the word "monk'' in reference to male members of religious orders other than the monastic orders.

"In the Western Church today there are four monastic orders: Benedictine, Cistercian, Trappist, and Carthusian."

"The Order of St. Benedict, or Benedictine Order, is named for the Italian abbot Benedict of Nursia (c.480-c.547), who compiled a rule for communal life in a monastery. The Rule of St. Benedict, which consists of a prologue and seventy-three short chapters, provides spiritual guidance and valuable instructions for maintaining a daily monastic routine of communal worship at the Divine Office, personal prayer, work, and study. Over the following centuries, a growing number of monasteries observing different monastic rules adopted the Rule of St. Benedict.

"Contemporary with the eleventh-century beginnings of the Cistercian Order and the Carthusian Order was the formation of communities of Augustinian canons, who were clergy attached to a cathedral or collegiate church. The Oxford scholar R. W. Southern explains that 'the Augustinians made a formal break with the past. Their patron was neither St. Benedict nor any other of the traditional guides to the monastic life.'[5] Canons Regular look to St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) and a brief treatise in the form of a letter he wrote providing spiritual direction for sharing a common life.

Canons Regular

"The Order of Canons Regular gave rise in the twelfth century to the Order of Prémontré, or Premonstratensians, founded by St. Norbert (c.1080-1134), a former canon of the Xanten Cathedral. He established a community of religious at Prémontré, near Laon, in northern France. 'According to the narrative of the foundation,' explains Professor C. W. Lawrence, University of London, 'on Christmas Day 1121 the group took vows to live 'according to the Gospels and the sayings of the apostles and the plan of St. Augustine.'[6] The religious wore habits of unbleached wool and were known as the 'White Canons.' "

Friars

"In a drawing or painting where an anonymous, distant figure wears a habit that is summarily indicated and who, for example, is depicted in a generalized setting, such as a woodland or unidentified interior, the term 'male religious' would be prudent in titling the work and in describing the picture's subject matter.

"The word 'monk' should not be used in referring to artists who were themselves members of a religious order but who were not monks, such as Fra Angelico and Fra Bartolommeo, both Dominican friars, and Fra Filippo Lippi, a Carmelite friar."

Benedictines

Cistercians

Trappists

Carthusians

"In the eighth and ninth centuries, Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious unified the religious practices of the Frankish Empire, which established Benedict's Rule as the standard rule for monastic life. Thereafter, the Rule of St. Benedict became the basis of monastic observance in the Western Church."

"The observance of monastic life at the Abbey of La Trappe, in Normandy, in the seventeenth century had a profound influence on the development of Cistercian monasticism.

"Abbot Armand-Jean Le Bouthillier de Rancé, inspired by accounts of early monastic life in the deserts of Egypt and Syria, instituted a rigorous spiritual asceticism at La Trappe. The monks devoted long hours to personal prayer and meditation in addition to the communal worship in choir; maintained an abstemious diet with fasting; and practiced self-denial, penance, and strict silence.

"The Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 48, 'The Daily Manual Labor,' instructs that the monks be engaged in work during prescribed times of the day as a balance to the hours devoted to prayer. The Trappists emphasized manual labor in their interpretation of the monastic precept ora et labora, prayer and work.

"The rigorous regime at the Abbey of La Trappe was adopted by other Cistercian abbeys through the following century. The nineteenth century saw a further increase in the number of Trappist monasteries, including several in the United States. An independent branch of the Cistercian Order was established at a special chapter of the Trappist congregations held in Rome in 1892. The 'old' order, which comprised the Cistercian monasteries remaining apart from the Trappist congregations, became known as the Order of Cistercians of the Common Observance. The Trappist congregations that formed the new order acquired the name Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, familiarly called the Trappist Order."[3]

"The Carthusian Order combines the solitude of eremitic monasticism with the organization and structure of a monastic community observing a daily routine centered on meditation and prayer. The Order dates from 1084 when Bruno of Cologne, former chancellor and master of the cathedral school of Rheims, and six companions withdrew to a remote Alpine valley above Grenoble. The men had the support of Bishop Hugh of Grenoble, who led the small band into the mountains to find a site for their eremitic settlement. Bishop Hugh recorded in the foundation charter: 'Master Bruno and his brothers began to inhabit and to build the foundations of this hermitage, whose boundaries we have just specified.'[4]

"During the following centuries, Carthusian monasteries, called in English 'charterhouses', were founded in many parts of Europe. By comparison with the great expansion of the Benedictine and Cistercian Orders, the Carthusian Order remained relatively small due to the seclusion and austerity of the life of the hermit monks. Today, Carthusian monasteries number twenty-three worldwide.

"Carthusian monks live in solitude in hermitages connected to a cloister that leads to the monastery church. The monks assemble in choir for conventual Mass in the mornings, for Vespers in the late afternoons, and for the long night Office of Vigils, which in the Carthusian horarium is combined with the Office of Lauds. The Offices of Prime, Terce, Sext, None, and Compline are observed by the monks in their respective hermitages, where they meditate and pray; take their meals; work, study, and sleep, to be woken after midnight by the monastery bell calling the community for Vigils."

1. The Oxford scholar and Benedictine monk Dom Bernard Green read a draft of Roseman's manuscript and wrote in a gracious letter

to the artist: "You portray the background and the aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

2. Louis J. Lekai, The Cistercians (Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1977), pp. 11, 13.

3. Ibid., pp. 188, 189.

4. André Ravier, St. Bruno the Carthusian (San Francisco, Ignatius Press, 1995), pp. 11-14, 77.

5. R. W. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1982), p. 241.

6. C. H. Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism (London: Longman, 1984), p. 142.

7. Ibid., p. 192.

8. David Knowles, Christian Monasticism (London: Thames and Hudson, 1969), pp. 115, 116.

9. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages, pp. 286, 287.

10. C. W. Previté-Orton, The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History, 2 vol. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952), vol. II, p. 675.

11. Ibid., vol. I, p. 631.

12. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages, p. 1.

13. Wolfgang Braunfels, Monasteries of Western Europe-The Architecture of the Orders (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), p. 129.

to the artist: "You portray the background and the aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

2. Louis J. Lekai, The Cistercians (Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1977), pp. 11, 13.

3. Ibid., pp. 188, 189.

4. André Ravier, St. Bruno the Carthusian (San Francisco, Ignatius Press, 1995), pp. 11-14, 77.

5. R. W. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1982), p. 241.

6. C. H. Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism (London: Longman, 1984), p. 142.

7. Ibid., p. 192.

8. David Knowles, Christian Monasticism (London: Thames and Hudson, 1969), pp. 115, 116.

9. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages, pp. 286, 287.

10. C. W. Previté-Orton, The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History, 2 vol. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952), vol. II, p. 675.

11. Ibid., vol. I, p. 631.

12. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages, p. 1.

13. Wolfgang Braunfels, Monasteries of Western Europe-The Architecture of the Orders (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), p. 129.

3. Dom Henry,

Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978

St. Augustine's Abbey, Kent, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978

St. Augustine's Abbey, Kent, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

5. Father Ian,

Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Meditation, 1978

Mount St. Bernard Abbey, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 70 cm

Musée Ingres, Montauban

Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Meditation, 1978

Mount St. Bernard Abbey, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 70 cm

Musée Ingres, Montauban

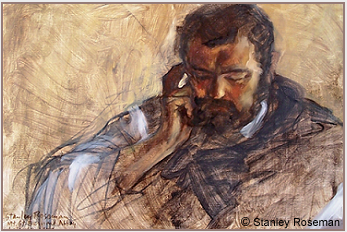

6. Portrait of a Carthusian Monk

in Prayer, 1984

St. Hugh's Charterhouse

Parkminster, England

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Teylers Museum, The Netherlands

in Prayer, 1984

St. Hugh's Charterhouse

Parkminster, England

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Teylers Museum, The Netherlands

Unlike today, monasteries then were closed to television cameras and documentary filmmakers, and the Internet with its vast information resources did not exist. Roseman's work on the monastic life brought a new awareness of the centuries-old and far-reaching contemplative tradition in Western culture.

2. Stanley Roseman drawing Trappist monks in choir,

Belgium, 1981.

Belgium, 1981.

"If the identification of a male figure wearing a religious habit is uncertain in a drawing or painting," Roseman further states, "it would be prudent to identify the figure as 'male religious.' Certain attributes or symbols help clarify an artist's intention as for the identity of the subject, such as a raven, associated with St. Benedict and the traditional black habit worn by Benedictine monks; or a skull, associated with St. Francis and Franciscan friars, who wear the traditional brown habit with a rope belt.

Presented below are paintings and drawings representing the four monastic orders in the Western Church. Roseman began his work on the monastic life in April 1978 in a Benedictine monastery, St. Augustine's Abbey, in Ramsgate on the coast of Kent. The monastery is named for St. Augustine of Canterbury, the sixth-century monk sent by Pope Gregory the Great to bring Roman Christianity to the British Isles and who later became the first Archbishop of Canterbury.

Dom Henry, Portrait of a Benedictine Monk

Roseman writes fondly of the Benedictine monk: "Dom Henry, a man of slender build and thinning, white hair, was seventy-three years old when he sat for me at St. Augustine's Abbey. His warm personality and kind and caring nature endeared him to Ronald and me. . . ."

The artist further recounts that the monks of St. Augustine's Abbey spoke of Dom Henry's 'deep and abiding faith' and that Dom Henry 'believed in the power of prayer, which he offered not only on behalf of those he knew but also for all humanity.'

In the portrait a luminous, pictorial space envelops the figure of the monk clothed in his black, Benedictine habit. The rapport between the artist and the monk is evident in the masterly rendered painting of Dom Henry, who looks directly out from the canvas. Here Roseman has created a deeply felt portrait with a powerful presence of a man who has dedicated his life to meditation and prayer in the search for God.

"As you undoubtedly already know, I have expressed to Monsieur Davis my admiration

for this work of art of profound insight and spirituality."

for this work of art of profound insight and spirituality."

- François Bergot

Chief Curator of the Museums of France

Director, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Chief Curator of the Museums of France

Director, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

"By the late thirteenth century, friars had become prominent university teachers. 'Both Dominicans and Franciscans surpassed their secular rivals in the universities,' explains the distinguished Professor C. W. Previté-Orton in his The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History.[10] The two-volume History is a scholarly, general overview of the Cambridge Medieval History and unlike the longer version, includes visual material, such as the illumination seen in fig. 128 with the caption 'Franciscan friar teaching,' from a thirteenth-century manuscript in the University collection.[11]

"In a further example of the identification of visual material, the front and back covers of the Penguin edition of Professor Southern's book reproduce illuminations from medieval manuscripts. Page one of the Penguin edition identifies the cover illustrations: 'marginal roundels from a French Book of Hours of c.1470 showing (front) Franciscan and (back) Carmelite friars, in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.' "[12]

Dom Henry was acquired in 1986 by the Chief Curator of the Museums of France, François Bergot, for the renowned collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, of which he was the Director. Davis, whose maternal ancestry is French, had introduced his colleague's work to the Rouen Museum.

In a cordial letter to Roseman to acknowledge the acquisition of the portrait Dom Henry, the Chief Curator of the Museums of France writes:

''The project is a splendid artistic collection, an historic record of a way of life never seen before on such a scale,'' enthuses Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, in its Sunday magazine color feature story in 1980 regarding Stanley Roseman's work on the monastic life.

4. Padre Gabriele, Portrait of a Cistercian Monk, 1998

Abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese, Italy

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Switzerland

Abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese, Italy

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Switzerland

Padre Gabriele, Portrait of a Cistercian Monk

In his journal Roseman speaks of the warm reception he and Davis received at Chiaravalle and the personal tour of the abbey by Padre Gabriele, the organist, with whom they shared a love of music and art.

Padre Gabriele is seen here in profile, (fig. 4), his fair complexion complemented by his black skullcap. Bold strokes of black and white chalks describe the monk's habit. With a painterly use of the chalks and a vivid presence of the individual, Roseman creates an impressive portrait. Roseman recounts:

"On Wednesday afternoon, Padre Gabriele thoughtfully gave Ronald and me an organ recital that included works by Bach, Schumann, and Vivaldi. In the red-brick, beautiful abbey church that integrates rounded arches of the Romanesque with early Piedmontese Gothic vaulting, Ronald and I sat enthralled listening to the memorable recital by the gifted musician and Cistercian monk.''

Father Ian, Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Meditation

Roseman has expressed serenity on the face of the Trappist monk, his right hand resting on his cheek and temple as he meditates at the end of his workday in anticipation of the monastery bell summoning the community to Vespers.

"Father Ian is for me an absolutely captivating work of art."

- Pierre Barousse, Curator

Musée Ingres, Montauban

Musée Ingres, Montauban

The Bibliothèque Nationale de France in a biographical essay on Roseman commends the artist for his "great talents as a draughstman" and praises his work in monasteries as "profoundly expressive of the individual and the interior life.''

Portrait of a Carthusian Monk in Prayer

"The Cistercian Order takes its name from the Abbey of Cîteaux founded 1098 in Burgundy by Robert of Molesme, who sought a contemplative life of asceticism and solitude inspired by the lives of the third- and fourth-century Christian eremites in the deserts of Egypt and Judaea. Abbot Robert and some twenty monks settled on a donation of land at a place called Cîteaux, in Latin Cistercium, about twenty kilometers south of Dijon.[2] The nascent community changed the traditional Benedictine habit of a black scapular and tunic to a black scapular worn over a tunic of 'white' or unbleached wool. The monks wore white cowls at the Divine Office in choir. Thus the Cistercians came to be known as the 'White Monks.'

"The early Cistercians emphasized the importance of manual labor by which to earn a livelihood, mainly from farming. The monks practiced austerity and self-denial, maintained an abstemious diet, and devoted hours to meditation and private prayer.

"Sixty years after Cîteaux's humble beginnings, the Cistercian Order comprised some three hundred and forty monasteries. The ascetic spirituality of the White Monks attracted numerous adherents to the contemplative life from all strata of society. By the fifteenth century there were more than thirteen hundred Cistercian monasteries throughout Europe."

Mount St. Bernard Abbey, secluded in a part of Charnwood Forest in Leicestershire, was the first Trappist monastery where Roseman painted and drew at the outset of his work in 1978. Roseman writes:

St. Hugh's Charterhouse, known as Parkminster, located in the countryside of West Sussex, is the only Carthusian monastery in the British Isles today. The Prior, Dom Bernard, a tall, bespectacled Irishman and former physician in Dublin, graciously received Roseman and Davis at Parkminster in 1983 and invited them to return the following year, which marked the 900th anniversary of the founding of the Carthusian Order.

Brother Augustine, an amiable, bearded Dutchman, is the subject of the impressive portrait drawing in chalks on gray paper of the hooded hermit monk in prayer presented here, (fig. 6). Roseman recalls, "I drew Brother Augustine in choir, and I also drew him in his hermitage, where he kindly invited me for a walk in the beautiful, trellised garden he had designed, built, and cultivated - a meditative outdoor space in the confines of his hermitage.''

Portrait of a Carthusian Monk in Prayer and an equally fine portrait of Brother Augustine, also from the Order's ninth centenary year, are conserved in the Teyler Museum, the Netherlands. The museum houses a renowned collection of Italian Renaissance master drawings, including works by Michelangelo and Raphael, and the Seventeenth-Century Dutch School, notably drawings by Rembrandt.

The portrait drawings of the Carthusian monk from Parkminster joined earlier acquisitions of Roseman's work on the monastic life and on other subjects from his extensive corpus of drawings. In letter of November 1989 to Davis, the Curator Carel van Tuyll praises "the splendid portraits of monks" and concludes, ". . . it is a cause of profound gratitude on our part to be able to show such an excellent group of Mr. Roseman's drawings.''

- Carel van Tuyll, Chief Curator

Teylers Museum, The Netherlands

Teylers Museum, The Netherlands

"The carpenter, a stocky, bearded monk named Ian, thoughtfully made his shop available to me and provided me with wood and tools with which to build stretchers for my canvases. Mentioning that my maternal grandfather had been a carpenter established an immediate rapport between Ian and me.''

Father Ian, Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Meditation is conserved in the Musée Ingres, Montauban, whose collection originated with an important bequest by Ingres (1780-1867) of his paintings and drawings, as well as works by Italian and French old masters, to his hometown. The Museum's collection has since been augmented with works of modern art.

Roseman painted the superb portrait of Father Ian in the carpentry shop after the monk had finished his day's work, (fig. 5). With chiaroscuro modeling the artist renders the monk's face, dark hair, and beard. His head and shoulders are silhouetted against a summary background of warm earth tones.

© Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis, 2014 - All Rights Reserved

Visual imagery and site content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Visual imagery and site content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

In the entries that follow, Roseman offers a brief description of and quoted information from scholars on the Order of Canons Regular and the Mendicant Orders:

-The Times, London

Roseman and his colleague Ronald Davis had received a cordial letter of invitation from Abbot Gilbert Jones of St. Augustine's Abbey. Davis wrote letters to monasteries to introduce his colleague's work, to relate the artist's interest in monastic life as a prospective subject for his paintings and drawings, and to make a request for a sojourn. Abbot Gilbert writes enthusiastically that Roseman's prospective work on the monastic life "sounds most exciting and of course you may start off here. . . .''

From Roseman's work at St. Augustine's Abbey in 1978 is the oil on canvas portrait of Dom Henry, (fig. 3).

1998 commemorated the 900th anniversary of the Cistercian Order. That year Roseman drew the Cistercian monks at the Abbey of Chiaravalle, situated on the periphery of Milan. Chiaravalle, founded in 1135, derives its name from its motherhouse in France, the Abbey of Clairvaux, of which St. Bernard was the first abbot.

The question is often asked: What is the difference between a monk, a friar, and a canon regular? Roseman provides here brief explanations of different categories of male religious.