AN ARTIST'S JOURNAL

Edited and prepared for the Internet by Ronald Davis

VIGILS

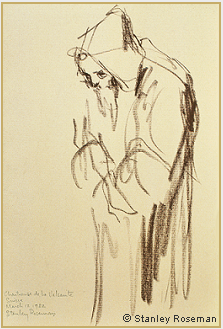

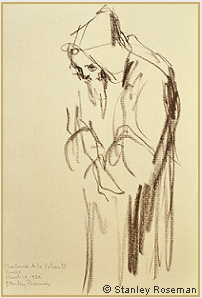

A Carthusian Monk at Vigils, 1982

Chartreuse de la Valsainte,

Switzerland

Bistre chalk on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Musée Ingres, Montauban

Chartreuse de la Valsainte,

Switzerland

Bistre chalk on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Musée Ingres, Montauban

"At midnight I rise to praise you, O Lord," states the Prophet in the Book of Psalms. Psalmody is the foundation of the Divine Office, which is central to the monastic life. Vigils, or the Night Office, is the first and the longest of the canonical hours. Roseman drew at Vigils in monasteries of the Benedictine, Cistercian, Trappist, and Carthusian Orders, the four monastic Orders of the Western Church.

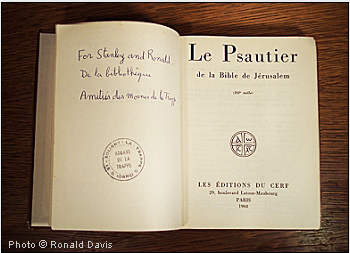

2. Title page of the Book of Psalms.

The librarian Frère Benoît, who kindly assisted the artist and his colleague in their research and study in the monastery library, inscribed the book on behalf of the monks. The inscription reads:

"For Stanley and Ronald,

De la bibliothèque

Amitiés des moines de La Trappe."

De la bibliothèque

Amitiés des moines de La Trappe."

"The desert settlement of Qumran, near the Dead Sea, was a center of monastic life in Judaism from the second century BC to the first century AD. The Dead Sea Scrolls include the Rule of the Community and accompanying texts that relate the communal life at Qumran: adherence to obedience, celibacy, and self-denial, the solemn ritual of the common meal taken in silence, the daily round of worship with the singing of the Psalms, and the lengthy vigil in the night.[6]

A gift copy of the Book of Psalms given in friendship from the monks of the Abbey of La Trappe to Stanley Roseman, of the Jewish faith, and Ronald Davis, of the Roman Catholic faith.

"At midnight I rise to praise you, O Lord'' - from Psalm 119

"The Therapeutae, Jewish eremites contemporary with the Qumran community, are the subject of Philo of Alexandria's treatise The Contemplative Life. The Therapeutae, whose main settlement was near Alexandria, lived in solitude in hermitages and observed a regime of prayer and reading and studying the Holy Scriptures. On the Sabbath, the hermits met in a sanctuary for a sermon given by an elder. Every seven weeks, as seven was regarded as a sacred number, the hermits assembled for a discourse and common meal followed by a vigil with prayers and singing until dawn.[7]

"The Lives of the Desert Fathers (Historia Monachorum in Aegypto), a fourth-century, contemporary account of Christian monks and hermits living in the Egyptian desert, records the vigils kept by those pious men.[8]

''The Prophet affirms in the Book of Psalms, 'At midnight I rise to praise you, O Lord' and 'Seven times a day I praise you.' This Biblical call to prayer from Psalm 119, 'In Praise of the divine Law,' gives monastic life its definitive form and structure.[2] The monastery bell tolls the Night Office, or Vigils, and the daytime Offices of Lauds and Prime in the early morning, Terce at mid-morning, Sext at midday, None in the early afternoon, Vespers in the early evening, and Compline at the close of the day.

"In my reading and study on the monastic life," recounts Roseman, "I learned that the Night Office observed in monasteries today has a precedent in Judeo-Christian early monastic traditions in the Middle East.

Vigils in Judeo-Christian early Monastic Traditions

3. Chartreuse de la Valsainte, with the Hermitages of the Carthusian Monks.

Switzerland, winter 1982

Switzerland, winter 1982

The Carthusian Order provides for the solitary life of the hermit within the context of a monastic community. The Chartreuse de la Valsainte was founded in 1295 in a secluded valley in the Gruyères range of the Swiss Alps. In the winter of 1982 Roseman and Davis received a cordial invitation from the Prior Dom Augustin Tönz, who writes: "We thank you heartily for your interest in monastic life. . . . Looking forward to receiving you here. . . . We pray with you for the Lord's choice blessings for yourselves and your work.''

Roseman drew at Vigils when the hermit monks gathered in choir to chant the Psalms, read from the Holy Scriptures, and prayed in silence during the long Night Office of two and a half to three hours. Presented here is A Carthusian Monk at Vigils, 1982, (fig. 4), conserved in the Musée Ingres, Montauban. The museum's renowned collection grew from a bequest by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), whose well-quoted maxim asserts: "Drawing is the integrity of art.''

In this deeply felt drawing of Brother Louis in prayer at Vigils, the artist has rendered the standing figure in bistre chalk on beige paper, which suggests the color of the Carthusian habit of undyed wool. The subtle gradations of the single chalk range from the fine description of the hermit's face and beard to bold strokes that define shadows from the fall of light on the hood, down the shoulder and arm, and under the sleeve of the habit. With an economy of line, Roseman has created a drawing of spiritual intensity in the depiction of the hermit monk in prayer in the night.

4. A Carthusian Monk

at Vigils, 1982

Chartreuse de la Valsainte,

Switzerland

Bistre chalk on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Musée Ingres, Montauban

at Vigils, 1982

Chartreuse de la Valsainte,

Switzerland

Bistre chalk on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Musée Ingres, Montauban

Acquiring A Carthusian Monk at Vigils for the Musée Ingres in 1986, the distinguished curator Pierre Barousse praises the "very beautiful drawing" in letter of appreciation to Stanley Roseman. The Curator of the Musée Ingres further writes: "I am, for what is meaningful to me, very sensitive to the purity and the profound interiority expressed in this work of art.''

The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University, conserves a related drawing of Brother Louis, A Carthusian Monk Asleep in his Cell, 1982. The artist drew the hermit monk taking a siesta. In letter of acquisition Dr. Kenneth Garlick, Keeper of Western Art, Ashmolean Museum, writes to Ronald Davis and praises "that fine drawing of the Carthusian monk asleep in his cell by Stanley Roseman." (The drawing is presented on the website stanleyroseman-monasticlife.com. See "Benedictines, Cistercians, Trappists, and Carthusians," Page 5 - "Carthusians." See also correspondence from Brother Louis to Roseman and Davis on the page "Correspondence from the Monasteries.")

© Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis, 2014 - All Rights Reserved

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Roseman's interest in the monastic life, his studies on the subject, and the encouragement of those whom he came to know in the monastic world led the artist to write a text to accompany his work in monasteries.[1] Roseman writes of the ancient Judeo-Christian tradition of psalmody in monastic life:

"The Book of Psalms, or Psalter, consists of 150 Psalms organized into five books, as with the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Old Testament.[3] Psalm 119, the longest Psalm, is divided into twenty-two stanzas. Each stanza has eight verses, of which the first verse begins with a letter of the Hebrew alphabet.

"St. Benedict in Chapter 16 of his Rule quotes the Prophet's call to prayer and affirms 'this sacred number of seven' will be fulfilled by observing the seven daily offices and Vigils in the night. In following chapters St. Benedict specifies which Psalms are to be sung at the canonical hours and allocates time for studying the Psalms.[4]

"Chapter 19 of the Rule concerns the discipline of singing the Psalms. In choir, the Psalms are sung in the ancient tradition from the Temple and Synagogue of antiphonal chanting, by alternate choruses or singers. Benedict instructs that the Psalms sung in the presence of God are to be sung in such a way that 'there is complete harmony between the thoughts in our minds and the meaning of the words we sing.' ''[5]

1. The Oxford scholar and Benedictine monk Dom Bernard Green read a draft of Roseman's manuscript and wrote in a gracious letter

to the artist: "You portray the background and the aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

2. The Psalter is comprised of one hundred and fifty Psalms. Psalms 10 to 148 in the Hebrew Bible are one number ahead of the Greek

Septuagint and Latin Vulgate Bibles. The Greek and the Vulgate combine Psalms 9 and 10 as well as Psalms 114 and 115,

while separating into two parts each Psalm 116 and Psalm 148.

3. Klaus Seybold, Introducing the Psalms (Scotland: T&T Clark, 1990), pp. 16-23.

4. The Rule of St. Benedict uses the numbering of the Psalms in the Vulgate Bible.

5. The Rule of St. Benedict, trans. Abbot David Parry, O.S.B., Households of God (London: Darton, Longman &Todd, 1980), and

Abbot Patrick Barry, O.S.B., St. Benedict's Rule (Ampleforth Abbey Press, 1997).

6. C. H. Geza Vermes, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1962),

The Community Rule, pp. 97-123.

7. Philo of Alexandria, The Contemplative Life and selected writings, trans. David Winston (New York: Paulist Press, 1981), pp. 41-57.

8. The Lives of the Desert Fathers, trans. Norman Russell (London & Oxford: Mowbray, 1981), pp. 13, 15.

9. Psalm 51 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 50 in the Vulgate.

10. The Rule of St. Benedict, trans. Abbot David Parry, O.S.B., Households of God.

11. Psalm 95 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 94 in the Vulgate.

to the artist: "You portray the background and the aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

2. The Psalter is comprised of one hundred and fifty Psalms. Psalms 10 to 148 in the Hebrew Bible are one number ahead of the Greek

Septuagint and Latin Vulgate Bibles. The Greek and the Vulgate combine Psalms 9 and 10 as well as Psalms 114 and 115,

while separating into two parts each Psalm 116 and Psalm 148.

3. Klaus Seybold, Introducing the Psalms (Scotland: T&T Clark, 1990), pp. 16-23.

4. The Rule of St. Benedict uses the numbering of the Psalms in the Vulgate Bible.

5. The Rule of St. Benedict, trans. Abbot David Parry, O.S.B., Households of God (London: Darton, Longman &Todd, 1980), and

Abbot Patrick Barry, O.S.B., St. Benedict's Rule (Ampleforth Abbey Press, 1997).

6. C. H. Geza Vermes, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1962),

The Community Rule, pp. 97-123.

7. Philo of Alexandria, The Contemplative Life and selected writings, trans. David Winston (New York: Paulist Press, 1981), pp. 41-57.

8. The Lives of the Desert Fathers, trans. Norman Russell (London & Oxford: Mowbray, 1981), pp. 13, 15.

9. Psalm 51 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 50 in the Vulgate.

10. The Rule of St. Benedict, trans. Abbot David Parry, O.S.B., Households of God.

11. Psalm 95 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 94 in the Vulgate.

AN ARTIST'S JOURNAL

An Audience with Pope John Paul II

An Invitation to Draw at the Metropolitan Opera

On Portraiture

Vigils - "At midnight I rise to praise You, O Lord" - from Psalm 119

Roseman and Davis were warmly welcomed at La Valsainte. The Prior Dom Augustin and the retired Prior Dom Nicolas Barras were greatly encouraging to the artist in his work on the monastic life, as were members of the community whom the artist came to know. Roseman recounts:

"Dom Augustin thoughtfully introduced me to Brother Louis, a monk of advancing years and whom the Community revered as a holy man. The Prior gave me permission to draw the hermit monk in his cell. There he read, wrote, and studied, took his meals, and meditated and prayed.''

Roseman recounts: "The friendship that grew from the days I visited Brother Louis in his cell was an enriching experience for my art and my life. His correspondence with Ronald and me over the years has meant very much." In correspondence with Roseman and Davis in December 1985, Brother Louis concludes his letter: "God bless you and help you to fulfill well your lifework. . . . I keep you always included in my prayers."

Hermit Monks in the Swiss Alps

The Abbey of La Trappe - Fountainhead of Trappist Monasticism

5. Abbey of La Trappe

Coat of Arms

Coat of Arms

Roseman's long and creative association with the Abbey of La Trappe began in 1979. Davis, who wrote to the monasteries to introduce his colleague and explain their request for a visit, received a cordial letter from Frère Élie (Elijah) writing on behalf of Abbot Dom Gérard Dubois and the Community: "It is with great pleasure that we shall receive your friend Stanley Roseman and yourself in our monastery."

During the following two centuries, other Cistercian abbeys took up the regime at La Trappe, and in 1892, at a special chapter in Rome, a separate branch of the Cistercian Order was formed, acquiring the name Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, also known as the Trappist Order.

Roseman recounts: "On the afternoon of June 4th, with the dates for our sojourn confirmed, Ronald and I arrived at the Abbey of La Trappe, situated in the rural countryside of Normandy. The tall, neo-Gothic church tower rose above the complex of living quarters, workshops, guest house, gatehouse, and numerous farm buildings that accommodated a large dairy herd, a main source of the monastery's income.

"The warm welcome and gracious hospitality we received from Abbot Gérard and the monks and their great encouragement to Ronald and me was especially meaningful as the Abbey of La Trappe is the fountainhead of Trappist monasticism.''

6. The Abbey of La Trappe

Normandy,1979.

Normandy,1979.

The Cistercian Order dates from 1098 with the founding of the Abbey of Cîteaux in Burgundy. In the seventeenth century the Abbey of La Trappe in Normandy was the center of a growing movement of rigorous, spiritual asceticism. The hours that the monks of La Trappe devoted to chanting of the Psalms and reading from the Scriptures at the Divine Office in choir were supplemented by extensive private prayer, meditation, and manual labor. The monks maintained an abstemious diet, practiced penitence, and observed strict silence within the cloister.

Roseman and Davis returned to La Trappe later that summer after sojourning with the Benedictine monks at the Abbey of Solesmes, in the département of the Sarthe; and the Abbey of Le Bec, in Normandy. After further travels to the Abbey of Fleury, along the Loire; the Abbey of Cîteaux; and monasteries in Spain, the artist and his colleague returned to La Trappe in October.

In ongoing correspondence, Frère Elie writes in autumn 1982, "Dear Stan and Ron, I read with pleasure that you intend to visit La Trappe again in the near future. All of us will welcome you heartily and in the meantime, send you our very best wishes. Affectionately Frère Elie.'' Roseman and Davis returned to La Trappe in December, and the artist resumed drawing the monks at prayer, work, and study.

Vigils at the Abbey of La Trappe

"As was my custom for drawing at Vigils in monasteries, I prepared my folios of drawing paper and box of chalks before I went to bed and set my alarm clock. At La Trappe, I rose at 3:15 A.M., washed, dressed, and - being that it was December in Normandy - put on my parka, gathered my drawing materials, and went to the church.

"I took a seat in one of the pews, opened my drawing book and box of chalks, selected a stick of chalk, and began drawing. In the dimly lit church, several monks stood or knelt in side chapels, others came to sit or kneel in the pews or choir stalls to pray and meditate. Despite the cold, it was inspiring to be there in the night with the monks, whose encouragement of my work on the monastic life I sincerely appreciated.

"At the tolling of the monastery bell at 4:15 A.M., the monks came forth from the side chapels and nave of the church and in from the monastery and took their places in choir. When all had assembled, Abbot Gérard tapped his ring signaling the cantor to begin the invocation from Psalm 51: 'Seigneur, ouvre mes lèvres,' ('Lord, open my lips,'). And the monks responded in unison, 'et ma bouche publiera ta louange' ('and my mouth shall proclaim your praise.')''[9]

In this intimate portrait, calligraphic strokes and tonal passages of bistre and black chalks establish a pyramidal composition in the depiction of the figure. A complementary geometric leitmotif of circular shapes and forms defines the monk's round face, round-rimmed eyeglasses, skull cap, and voluminous sleeves.

Père Robert leans forward, his arms rest on the back of a pew, his hands tucked into the sleeves of his cowl. The rendering of light and shade in blended tones, or sfumato, of bistre and black chalks with subdued white highlights and the reserved areas of gray paper give the work a nocturnal ambiance. In this superb drawing Roseman conveys a deep spirituality of the Trappist monk in prayer and meditation in the night.

The drawing Père Robert at Vigils, (fig. 7, above), in the collection of the Graphische Sammlung Albertina was included in the museum's exhibition Stanley Roseman-Zeichnungen aus Klöstern (Drawings from the Monasteries), 1983. Roseman is the first American artist to be given a one-man exhibition at the Albertina, which conserves nine drawings by the artist. The museum's eminent Director Dr. Walter Koschatzky, making his first acquisition of Roseman's drawings for the Albertina in 1978, writes in a cordial letter to Ronald Davis:

7. Père Robert at Vigils, 1982

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Albertina, Vienna

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Albertina, Vienna

- Dr. Walter Koschatzky, Director

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

Père Robert at Vigils, 1982, (fig. 7), was acquired the following year by the Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, containing a world-renowned collection of master drawings.

Recounting his return to the Abbey of La Trappe in 1982, Roseman writes:

Roseman also drew Père Robert in the tailor shop, where as the artist recounts: "An immediate rapport was established between us when I mentioned to Père Robert that my paternal grandfather was a tailor in New York City."

The conclusion of the communal worship at the Night Office at La Trappe is followed by personal prayer. Roseman further relates:

"After the last Psalms were sung; the Psalters, closed; and the candles on the altar, extinguished, the monks remained for an additional half hour for personal prayer and meditation in the darkened church. Some of the monks dispersed from choir to the side chapels, while others went to sit on the benches in the rear of the church or in the pews. I closed my drawing book and box of chalks, placed them by my side, and like the monks, I immersed myself in meditation and prayer."

A meaningful Letter to the Artist from the Abbot of La Trappe

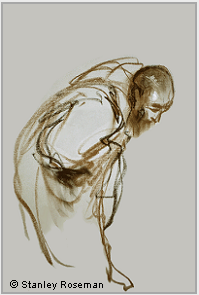

Roseman drew A Trappist Monk Bowing in Prayer, (fig. 9), when he and Davis sojourned at the Abbey of La Trappe in December 1982. They presented the monastery with a gift of the artist's drawings which includes the work seen here. The gift of the drawings was made in appreciation to Abbot Gérard and the Community for their gracious hospitality and encouragement to the artist.

The revered Abbot of La Trappe writes in a deeply moving letter (here translated from the French) to Stanley Roseman, who is of the Jewish faith:

"I thank you again for your good wishes and for the drawings

that you have generously given us.

They will be symbols of the bond that unites us,

regardless of the differences of language, religion, and life-style.

But in the most profound essentials, we are as one.''

that you have generously given us.

They will be symbols of the bond that unites us,

regardless of the differences of language, religion, and life-style.

But in the most profound essentials, we are as one.''

- Abbot Gérard Dubois

Abbot of La Trappe

Abbot of La Trappe

9. A Trappist Monk

Bowing in Prayer, 1982

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Collection Abbey of La Trappe

Bowing in Prayer, 1982

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Collection Abbey of La Trappe

The beautiful drawing is rendered in fluent lines of bistre and black chalks depicting the voluminous cowl, complemented by detail modeling of the Trappist monk's face and beard, with highlights of white chalk on the forehead. The reserved areas of the gray paper evoke both form and spacial dimension. Roseman eloquently expresses in the drawing the monk's reverence for God.

Drawings from the Monasteries

"You have delivered to me two drawings by Stanley Roseman, which I have acquired for the Albertina.

I thank you and want to express my conviction that the artist is an outstanding draughtsman and painter

to whom much recognition and success are due.''

I thank you and want to express my conviction that the artist is an outstanding draughtsman and painter

to whom much recognition and success are due.''

You are cordially invited to visit

www.stanleyroseman-monasticlife.com

www.stanleyroseman-monasticlife.com

"For he is the Lord our God:

we are his people and the sheep of his pasture."

we are his people and the sheep of his pasture."

- from Psalm 95, sung at Vigils

In his text to accompany his work in monasteries, Roseman writes: "The Rule of St. Benedict contains four chapters on Vigils: Chapter 8, 'On the Divine Office During the Night;' Chapter 9, 'The Number of Psalms to be Said at the Night Office;' Chapter 10, 'The Arrangement of the Night Office in Summer;' and Chapter 11, 'The Celebration of Vigils on Sundays.' Winter was calculated from the first of November to Easter, and summer, from Easter to November. In Chapter 10, St. Benedict instructs that due to the shorter nights in summer, the three readings from the Scriptures and other spiritual writings are to be replaced by one reading. 'Instead of these three readings, one from the Old Testament is to be recited by heart, followed by a short responsory.'[10] St. Benedict further instructs that 'in winter and summer, no less than twelve Psalms are to be sung at Vigils, not counting Psalms 3 and 95,'[11] which according to the Rule are always included."

8. Two Trappist Monks

at Vigils, 1982

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Michigan

at Vigils, 1982

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Michigan

In this superb drawing the Trappist monks are wearing voluminous, woolen cowls with long sleeves that cover their arms and hands. The predominant use of bistre chalk, blended tonal passages of bistre and black chalks, and reserved areas of the gray paper imbue the drawing with a nocturnal quality, as in the related drawing above from La Trappe, (fig. 7), Père Robert at Vigils, in the collection of the Albertina.

- from Psalm 3, sung at Vigils

Roseman drew Two Trappist Monks at Vigils, (fig. 8), at the Abbey of La Trappe in December 1982. Frère Marc, the ascetic, bearded monk who stands in the foreground of the drawing was "a kind and caring guestmaster,'' writes the artist, such as when he recounts: "Frère Marc thoughtfully told me that the church was cold and to dress warmly, especially when I draw at the long Night Office."

"Deliverance belongs to the Lord: O let your blessing be upon your people.''

The chiaroscuro modeling in black and bistre chalks, with subdued white highlights on the face, eyeglasses, and cranium of Frère Marc, brings the figure forward in pictorial space. The monk stands with head bowed and eyes lowered. His confrere in choir is drawn with fluent lines and transparent tones of bistre chalk. He leans forward, his right arm raised and head upturned towards the altar. In this compelling composition, Roseman expresses the individuality of the two Trappist monks, each absorbed in prayer at the Night Office.